Descriptive set theory nowadays is understood as the study of definable subsets of Polish Spaces. Many of its problems and techniques arose out of efforts to answer basic questions about the real numbers. A prominent example is the Continuum Hypothesis ():

Early approaches tried to show that holds for a number of sets with an easy topological structure.

For closed sets, the situation is less clear. Given a set , we call a limit point of if

where denotes the standard -neighborhood of in

In other words, a perfect set is a closed set that has no isolated points. We can also deduce that for a perfect set , every neighborhood of a point contains infinitely many points from .

Cantor set

Obviously, itself is perfect, as is any closed interval in . There are totally disconnected perfect sets, such as the middle-third Cantor set in

Hint

- Argue it suffices to construct an injection from (the set of all infinite binary sequences) into the perfect set.

- Start with any point in the perfect set and open neighborhood . Use the perfect set property to find two points distinct from and each other in .

- These points will ‘guide’ the mapping: All sequences in starting with 0 will be mapped to a point close to , while all sequences starting with 1 will be a mapped to a point close to .

- Now iterate with and in place of .

Proof

Let be perfect. We construct an injection from the set of all infinite binary sequences into . An infinite binary sequence can be identified with a real number via the mapping

Note that this mapping is onto. It follows that the cardinality of is at least as large as the cardinality of . The Schröder-Bernstein Theorem (for a proof see e.g. Jech (2003)) implies that .

To construct the desired injection, choose and let . Since is perfect, is infinite. Let be two points in , distinct from . Let be such that , , and , where denotes the closure of .

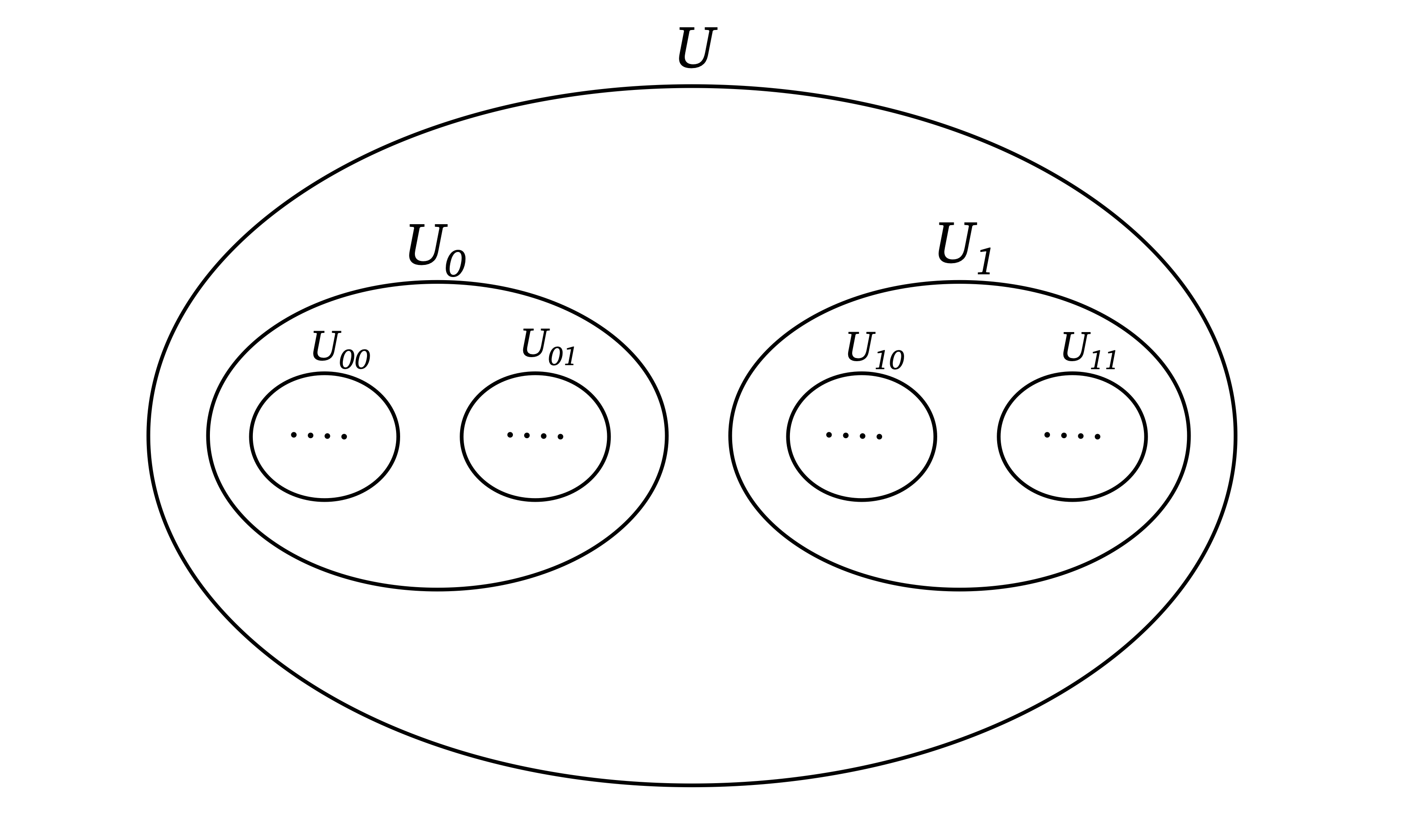

We can iterate this procedure recursively with smaller and smaller diameters, using the fact that is perfect. This gives rise to a so-called Cantor scheme, a family of open balls satisfying certain nesting conditions. Here the index is a finite binary sequence, also called a string. A Cantor scheme is defined by the following properties.

- , where denotes the length of .

- If is a proper extension of , then .

- If and are incompatible (i.e. neither extends the other), then

- The center of each , call it , is in .

Figure 2:Nested structure of a Cantor scheme

Let be an infinite binary sequence. Given , we denote by the string formed by the first bits of , i.e.

The finite initial segments give rise to a sequence of centers. By properties (1.) and (2.), this is a Cauchy sequence. By (4.), the sequence lies in . Since is closed, the limit is in . By (3.), the mapping is well-defined and injective.

Thus, to show that a set of reals has the same cardinality as , it suffices to show the set contains a perfect subset. The next theorem establishes that the Continuum Hypothesis holds for all closed subsets of .

Hint

Consider the set of condensation points, i.e. the set of all points for which any open neighborhood has uncountable intersection with the given closed set.

Proof

Let be uncountable and closed. We say is a condensation point of if

Let be the set of all condensation points of . Note that , since every condensation point is clearly a limit point and is closed.

Furthermore, we claim that is perfect. It is straightforward to verify that is closed. To see that every point of is a limit point, suppose and . Then, by assumption, is uncountable. We would like to conclude that is uncountable, too, since this would mean in particular that is infinite. The conclusion holds if is countable.

To show that is countable, assume that . Then, for some , is countable. We can find an interval that contains and has rational endpoints. There are at most countably many intervals with rational endpoints and hence for each there are at most countably many choices for . Thus, we have

The right hand side is a countable union of countable sets, hence countable.

Finally, the fact that is countable also implies that is non-empty. We have therefore verified that is a perfect subset of .

It follows that the Continuum Hypothesis holds for closed sets.

The results of this lecture give us a blueprint on how to verify the Continuum Hypothesis for a given family of sets (of reals):

A family of sets (of reals) has the perfect set property if every set in is either countable or has a perfect subset.

- Jech, T. (2003). Set Theory. Springer-Verlag.